.

A blog for fiction writers and impending writers. An editor’s perspective.

A blog for fiction writers and impending writers. An editor’s perspective.

• Next post • Previous post • Index

Active Writing (Part 2): Active Language (Grammar, sentence structure, linguistics)

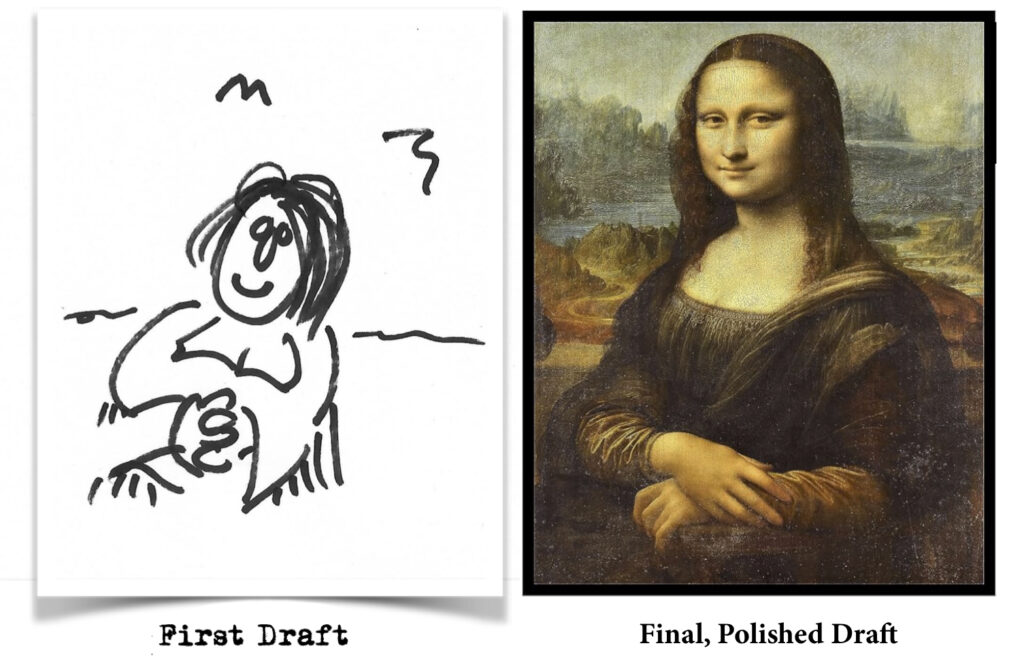

To recap: I look for active writing—the life of a novel—on three distinct levels: 1. Voice. 2. Language. 3. Plot.

I’ll keep this simple, for both your sake and mine. If you need a grammar lesson, we’re both in the wrong place.

But, in the English language (as compared to, say, Kayabi, and whatever Yoda spoke), the simplest way to invoke energy and emotion into sentence structure is typically: Subject (S) + Verb (V) + Object (O).

Thus (SVO): John kissed Mary.

John (S) + kissed (V) + Mary (O). Or else: Laura (S) + killed (V) + the snake (O).

As opposed to Mary was kissed by John. Or, The snake was killed by Laura. Or the heinously passive: It was the snake that was killed by Laura.

By rearranging the sentence structure to the less energetic Object + Verb + Subject (OVS), a writer is placing the action’s instigator at the end of the sentence and slightly altering the emphasis. And in longer, more complex sentences, both nuance and structure can become uncomfortably apparent. You’re also clogging your story with extremely passive verbs; “was” and “were;” unnecessary prepositions, pronouns, articles and the so-called “little” phrases (e.g.; it would, that were, of the, by which). Such utterly unexciting placeholders act as a buffer between words and action.

For instance, a subtle but distinct difference exists between: Prince Clarion crushed the giant orc’s head and The head of the giant orc was crushed by Prince Clarion. While both structural formats can and will ultimately co-exist in your novel, play with the most active structure first. This is especially important in scenes of passion, action, high tension or terror.

Rule #6: The Jumping Cow Rule (Active vs. Passive Voice). I learned this tenet once upon a time in Eng. Lit. 101. The rule remains the connective tissue of everything I write:

Active (SVO): The cow jumped over the moon.

Passive (OVS): The moon was jumped over by the cow.

Bad passive (WTF): It was the moon that was jumped over by the cow.*

An active/passive correction can be as simple as choosing a more active verb, or as complex as restructuring a sentence. For instance:

Uninspired but acceptable: The moon was bright.

Better: The moon burned brightly.

Or even the more elaborate: The full moon blazed with an intensity that illuminated the village in a mystical chalky sheen.

Because once a writer can identify the difference between active and passive writing, one seldom returns to the excruciatingly mundane.

While I doubt any author can (or should) write an entire novel strictly using SVO sentence structure, I do suggest keeping this grammatical sequence as a staple tool for active writing. And, no, simply because Hemingway frequently used passive voice, you may not. And, no, because David Foster Wallace did so in present tense—“I am this” and “I am that”—you may not. “It was…” is glaringly overused in modern fictive writing. More often than not, excessive passive voice is a sign of tired writing. Meaning your brain’s full. Put down your pencil. Take a walk. Take a nap. Clean the house. Because most “it” usage can transmogrify into far more descriptive prose. Occasionally, it fits such sentence structure may suffice your needs, but most often, it does not your words can be easily rearranged with far more passion and creativity.

A good many novice writers (and even published pro’s) can occasionally slip into a steady flow of passivity. Be on the constant lookout for:

It was a dark and stormy night. Linda was sleeping. There was a noise that awakened her with a start. What was that? she wondered. Was somebody standing outside her door. Was it her husband, Teddy? It was because she didn’t know that she tiptoed to the door. There was only silence beyond the door. Linda was scared and we, dear reader, are ready to close this book forever.

So look closely for any steady stream of passive sentence structure beginning with tired phraseology: It was, They were, There was—and the dreaded It was because…. Each of these sentences can be actively rearranged (and the more you begin to do so, the easier such restructuring becomes).

I’ve occasionally come upon an interesting side-effect of passive language. If a writer twists and contorts various, meaningless phrases long and hard enough, the words sometimes almost sound correct. In fact, a writer may even be convinced that such lavish flow of language sounds positively Shakespearean. But this style of writing is roughly akin to spritzing a pig in expensive French perfume. He may smell nice for awhile, but you still won’t want to kiss him.

For example, this sentence still smells like a pig: Of that substance to which Richard was most disinclined ever to confront, he promised himself never again to touch it to his lips.

Keep your message simple. What’s the idea you’re trying to impart here? Basically, it’s that: Richard hated chocolate, right?

So how might one say that creatively, and yet without losing your basic premise? How about: Richard couldn’t understand the world’s love affair with chocolate. On his tongue, the candy oozed like motor oil, and tasted, to his best perception, like dirty butter.

A simple thought, distinctly perceived, clearly transmitted. Active, not passive.

– – – – –

* Exceptions always exist, BTW. You’ll occasionally, eventually find this particular phraseology a perfect fit for your needs and, by all means, use it. However, if you find yourself using this grammatical gremlin as a basic structural pattern—then no, you’re not infusing sufficient excitement into your writing. You’re using passive language way too often..

• Next post • Previous post • Index

.